Utah's landscape is incredibly diverse and so is its wildlife. However you like to experience nature, Utah offers plenty of options from relaxed wildlife viewing and photography, to active adventures like rafting, backpacking or hunting. Any time you’re outdoors, you may have the opportunity to see some of the state’s over 700 wildlife species, 250 species of birds, 620 species of spiders, 9 species of scorpions, so keep your eyes peeled. Mammals are the most abundant animal species in the state since they exist in almost all regions. There isn’t just one way to enjoy nature and wildlife. Lace up your hiking boots, grab your fishing pole, pack your binoculars, and get ready to enjoy! Remember safety should always be your first priority. Getting close to animals is dangerous for both the animal and you. Respect nature. Remember these are wild animals and some are poisonous.

Mammal species include mule deer, brown bear, mountain goat, antelope, mountain bison, black bear, wild horses,lynx, moose, long-tailed weasel, cougar, mountain lion, badger, gray wolf, bighorn sheep, llamas, coyote, elk, wolf, sage grouse, squirrel, mink, muskrat, ferret, gopher, otter, skunks, porcupine, raccoon, wolverine, shrews, pika, marmot, vole, rabbits, birds, swans, hawk, falcon, vulture, owls, blue heron, wild turkey, roadrunner, pelican, condor, bulfrogs, bats, and foxes. Also numerous species of spiders, snakes, scorpions, butterflies, moths, and bees. Reptiles like lizards, desert tortoise, gila monster, salamander, gecho, iguana, turtles, and many more species that call the state of Utah and its national parks home. As for lakes, rivers, and streams you can find several species of fish including whitefish, crappie, bluegill, trout, catfish, carp, june & bluehead sucker, and mollusks.

Stop and smell the roses, as the saying goes. That may work in the English countryside, but here in the Beehive State, it’s Utah wildflowers that deserve notice. Scene stealers like lupine, sego lilies, mountain sunflowers, columbine, and paintbrush share the stage with fragrant forests and gurgling creeks in the north, and desert breezes and red rock canyons to the south. Altogether, finding wildflowers is a rewarding, multi-sensory performance worth the hike. The optimal time to view Utah wildflowers depends on temperature and elevation. Wildflowers can bloom in Utah anytime between March and September. At higher-elevation meadows, peak season is June, July and August.

Utah is known as the Beehive State because the beehive is a symbol of hard work and industry. The state adopted the beehive as its official symbol in 1959, designated the honeybee as the state insect. Beyond the symbolism, Utah also has a diverse native bee population, with over 1,100 species documented. These native bees play a crucial role in pollination and are often more effective than honeybees. Utah is also home to various bumble bee species. Not all bees make honey. Most bees are solitary and do not live in hives. Bees use pollen and nectar as a food source. Most bees are not aggressive, meaning they rarely sting.

Flowers also bring out the butterflies and moths as they show us their colors. There are so many kinds of butterflies in Utah! Rocky Mountain states such as Utah rank as some of the best butterfly destinations in the United States. The east-west divide means that the eastern slopes of the state attract many of the eastern butterflies and the western slopes, valleys and fields support entirely different butterfly populations. Butterflies have been icons of peace and reverence for millennia. There are eight different families to which butterflies belong, at least 250 species of which are found in Utah.

The Bear River is the largest tributary to the Great Salt Lake. Its volume at times reaches 1.4 million acre feet of water. Beginning in Utah's Uinta Mountains, the swift-falling stream first heads north and then changes into a slow meandering stream in Wyoming. It then flows west into Idaho and south into Utah. After flowing nearly 500 miles, it finally empties into Bear River Bay of the Great Salt Lake, ending ninety miles from its place of beginning. Shoshoni Indians lived near the Bear River before Anglo settlement. They were primarily hunter/gatherers who occasionally traded and fought with Cheyenne, Crow, and Blackfoot tribes. The fur trade brought white trappers to the area. In 1812 Robert Stuart, returning from Astoria, Oregon, heard stories from white men on the Snake River of a river to the south; he was persuaded to take a look at what he later called Miller's River, named after his guide, Joseph Miller. William Sublette led a party in 1824 from the Green River to Soda Springs, the Bear River's northernmost point. So colorful were the stories of the Bear River that the trappers' rendezvous of 1825 and 1827 were held here. John Charles Fremont explored the area in 1843 and his report helped prepare the Mormons for their new life in the West. Some Mormons thought they were coming west to settle the Bear River Valley. They explored the mouth of the Bear in April 1848 in the Mud Hen, a fifteen foot skiff built from fir planks and launched in the Jordan River at Salt Lake City. The next year, Howard Stansbury and John W. Gunnison, U.S. Topographical Engineers, took Albert Carrington and a crew of men on a circumnavigational expedition of the Great Salt Lake. Their craft was left high on a mud flat in the Bear River Bay when a sudden April snowstorm nearly took their lives. In 1863, during the Civil War, Colonel Patrick Connor took troops north from Salt Lake to Cache Valley in order to chastise some Bannock (Shoshone) Indians who had been raiding emigrant wagon trains. Connor surprised the Indians' winter encampment on the Bear River and killed 250 Indians in what has come to be viewed as a controversial and terrible action. The James A Garfield, a paddle-wheeler, carried ore from the south shore of the Great Salt Lake up the Bear River as far as Corinne for transshipment by rail before 1874. Geologists John W Powell and GK Gilbert reported as early as 1878 that the Bear River waters would generate controversy. The truth of their foresight was proven when one of the first stream-gauging stations in the U.S. was established at Collinston in 1889. Farmers in Wyoming, Idaho, and Utah wanted as much water as they could get and power companies filed for rights. Coming close to Bear Lake but not part of it, the River was joined by an inlet in 1918 in order that river waters could be stored in the lake. Under the 1955 Bear River Compact water rights have been redefined and use is regulated more to the users' satisfaction.

The Colorado River is one of the most important water systems in the United States. Draining watersheds from seven western states, it is divided into two major districts, the Upper Basin comprised of Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico, and the Lower Basin formed by Nevada, Arizona, and California. With its headwaters in Wyoming and Colorado and its mouth (until recently) flowing into the Gulf of California, this river serves as a focal point for both prehistoric and historic events in the West. The Colorado courses through Utah in a southwesterly direction and has two major tributaries, the Green and San Juan rivers, with smaller, additional sources flowing in from east and west. During prehistoric times it constituted a permeable boundary between the Anasazi populations to the south and east, and the Fremont and western Anasazi populations to the northwest and west, respectively. The Anasazi farmed tributary canyons and alluvial bottom lands where soil was rich and water adequate. These early Indians also created a system of trails that crossed both the San Juan and Colorado rivers. Spanish and Anglo-Americans later used some of these paths in their exploration and settlement of the West. Historic Native American groups living along the Colorado include the Paiute in southwestern Utah, the Ute in southeastern Utah, and the Navajo south and east of the confluence of the San Juan and the Colorado. This latter group has a rich body of lore concerning the river, which they say has a female spirit name "Life Without End." She, and her male counterpart, the San Juan, form a protective boundary that skirts the reservation lands. In the past, Navajo ceremonies like the Blessingway provided protection for events and locations within this area, while beyond this line Enemyway and Evilway applied. Navajo raids across these rivers were a common occurrence during the 1850s and 1860s, and to a lesser extent in the 1870s. The Spaniards provided the first documented information about the Colorado, giving the river various names, such as El Rio de Cosninas, de San Rafael, and de Tizon. Various Spanish parties visited the river, the most famous one in Utah being the Dominguez-Escalante expedition in 1776. As the two padres returned to Santa Fe, New Mexico, through southwestern Utah, they came upon an old Ute trail in an area that appeared otherwise impassable. Chiseling steps and smoothing a path for livestock, the missionaries forded the river at what was called the Crossing of the Fathers, which now rests under the waters of Lake Powell.

It was not until 1869 and again in 1871-72, that the Colorado was fully mapped. John Wesley Powell's two expeditions, sponsored by the Smithsonian Institute and Congress respectively, charted the water's course from Green River, Wyoming, through the Grand Canyon and beyond. His ten and eleven man crews collected information and sailed their wooden boats down one of the most dramatic and roughest inland waterways in the United States. Many people in Utah came to cross or visit the river but, with the exception of Moab where the water was calmer and the flood plain wide, few came to stay. For instance, the Mormons built the Hole-in-the-Rock trail in 1880, but once across, they moved on to the quieter San Juan. Charles Hall, a year later, placed into service a thirty-foot ferry boat to handle the traffic on the route between Bluff and Escalante; insufficient business caused Hall's Crossing to close three years later. Even Hite City (1883), named after Cass Hite, a prominent prospector, was a boom and bust mining town on the Colorado that lasted only seven years. The 1930s and 1940s saw the introduction of a more profitable trade on the Colorado river running and tourism. Norman Nevills, for example, headquartered at Mexican Hat and turned the red waters of the San Juan and Colorado into green cash as recreation became increasingly important. Even with the introduction of the Glen Canyon Dam in the 1950s and Lake Powell in the 1960s, there was still plenty of white water and red rock for adventurous souls to find the isolation and excitement they desired. And later, when its tributaries were heavily committed to irrigation and culinary use, the Colorado remained a playground for kayakers, rafters, and tourists. Today, the Utah portion of the Colorado River continues to offer not only its water as a resource, but also its beauty and adventure to those who come to its banks.

The Escalante River is a tributary of the Colorado River. It is formed by the confluence of Upper Valley and Birch Creeks near the town of Escalante in south-central Utah, and from there flows southeast for approximately 90 mi (140 km) before joining Lake Powell. Its watershed includes the high forested slopes of the Aquarius Plateau, the east slope of the Kaiparowits Plateau, and the high desert north of Lake Powell. It was the last river of its size to be discovered in the 48 contiguous U.S. states. The river was first mapped and named by Almon Thompson, a member of the 1872 Colorado River expedition led by John Wesley Powell. It was named after Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, a Franciscan missionary and the first known European explorer of the region. In 1776, Escalante and his Spanish superior Francisco Atanasio Domínguez left from Santa Fe, New Mexico in an attempt to reach Monterey, California. During this journey, usually referred to as the Domínguez–Escalante expedition, Escalante and his companions passed by the Grand Canyon and were the first white men to enter Utah. Much of the Escalante River's course is through sinuous sandstone gorges. The river and the rugged canyons which drain into it form a key section of Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument. This spectacular region is a popular destination for hiking and backpacking. For most of the year, the Escalante River is a small stream, easily stepped across or waded. During spring runoff and the summer monsoon, however, the river can become a raging, muddy torrent ten to one hundred times bigger. In some years, the river can be run using kayaks or canoes (rafts are too large), but this requires both good timings — water which is too high or too low can make travel impossible, stranding boaters — and the willingness to portage boats several hundred vertical feet at the end of the trip.

The Green River was known to the Shoshone Indians as the Seeds-kee-dee-Agie, or Prairie Hen River. This name, in one version or another, was later adopted and widely used by the mountain men. The Green River is Utah's major stream. Its beginnings are in Wyoming, on the eastern slopes of the Wind River Mountains, and it makes a forty-mile loop through northwestern Colorado, but the majority of the course of the Green lies in Utah. The river is 730 miles long; approximately 450 miles of it are in Utah. The Green drains the entire northeast corner of Utah, or about one-quarter of the entire area of the state. The landforms drained by the Green in Utah range from the highest part of the state, in the Uinta Mountains, to some of the lowest, in the Uinta Basin. In its course through Utah, the Green drops from an elevation of approximately 6,000 feet above sea level at Flaming Gorge Reservoir to about 3,000 feet at its confluence with the Colorado. Shortly after entering Utah, the Green enters Flaming Gorge, the first of a long series of canyons. Flaming Gorge, Horseshoe, and Kingfisher canyons are short but scenic. Red Canyon, the next in the series, is about thirty miles long, and is now the site of Flaming Gorge Dam. After Red Canyon, the Green enters Browns Park, a large east-west trending basin, and flows through it for fifteen miles before crossing the Colorado border. The river flows through the northwest corner of Colorado for forty miles, through the Canyon of Lodore, and receives the waters of its largest tributary, the Yampa, while in Colorado. The Green re-enters Utah in the middle of Whirlpool Canyon, about five miles below its confluence with the Yampa. After passing through Island and Rainbow parks, the Green runs a short but turbulent seven miles through Split Mountain Canyon, which has the greatest fall of any of the canyons of the Green--almost twenty-one feet per mile--and consequently has some of the most difficult rapids on the entire river. Below the mouth of Split Mountain Canyon, the Green flows through the open, arid landscape of the Uinta Basin for more than 100 miles, unconfined by canyons and undisturbed by rapids. In the Uinta Basin two more large tributaries, the Duchesne River from the west and the White River from the east, join the Green, their mouths almost across from each other. The next canyons are Desolation Canyon and Gray Canyon, two back-to-back canyons that total 120 miles in length. Desolation is the deepest and longest of the canyons of the Green, while Gray (earlier known as Coal Canyon) is lower but narrower. The Green leaves Gray Canyon just above the town of Green River, Utah, and flows through an open area for about thirty miles before entering the last of the canyons it traverses, Labyrinth and Stillwater canyons. As the names suggest, these are quietwater canyons, where the river loops in sinuous curves around towering cliffs of sandstone. The Green meets its sister stream, the Colorado, at the end of Stillwater Canyon, in the middle of what is now Canyonlands National Park. The Green traverses several different vegetation and fauna zones during its course through Utah, ranging from high mountains in the north to slickrock deserts in the south. Pines, firs, and groves of aspen are common in the higher parts, while pinyon and juniper are predominant below the mountains. In the lower elevations, shadscale, sagebrush, cactus, and desert shrubs are most common. Cottonwoods, tamarisk, and willows are the predominant members of the riparian plant community throughout the river's length. Likewise, fauna follow typical life zones. Elk, deer, bighorn sheep, coyotes, rabbits, squirrels, and other small rodents, and an occasional bobcat or cougar are found along the Green. Snakes, lizards, toads, and other reptiles are common near the river, less common away from it. Bird life, especially along the river corridor, is abundant, as the river is part of the main north-south flyway for some waterfowl. It was not until 1869 that the Green River was surveyed and mapped by a scientific party.

The Jordan River is the northward-flowing, forty-mile-long waterway connecting Utah Lake on the south with the Great Salt Lake. Returning from California in June 1827, Jedediah Smith crossed the Jordan with some difficulty, noting in his journal that he was "very much strangled" in his attempt. This was probably a reference to the annual spring flooding of what normally is a rather slow-moving river; an occurrence which has been a matter of periodic concern to the area's inhabitants since the founding of Salt Lake City and surrounding communities. The river was named the "Western Jordan" in 1847 by Heber Kimball, soon after his arrival in Utah. He noted its resemblance to the Middle Eastern river of the same name: a river flowing from a "fresh water lake through fertile valleys to a dead sea." Western was soon dropped from the river's name. During construction of the Salt Lake Temple, granite blocks were floated down the river to the city. The Jordan was again used to float construction materials in 1869, this time floating logs and ties for use on the Central Utah Railroad. Almost from the beginning of settlement, the communities of Utah and Salt Lake valleys have used the Jordan to carry waste and sewage away to the Great Salt Lake. This created an understandable, albeit occasional, concern for the sanitary and aesthetic qualities of the river. After the river overflowed its banks in 1952, Salt Lake County built a diversion dam and the Army Corps of Engineers enlarged an already extant surplus canal. There followed a program of dredging and straightening the river channel to reduce the damage caused by periodic spring floods. Throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s the Jordan continued to be used as a waste disposal canal for area slaughterhouses, packing plants, mineral reduction mills, and laundries. In 1973 the Utah State Legislature created the Provo-Jordan River Parkway Authority to establish programs to enhance the natural quality of the river and to develop park and recreational facilities, water conservation projects, and flood control measures. By 1976 the Salt Lake Tribune was noting improvements in water quality and decreased industrial pollution, although some areas of the river still needed to be improved. Since the 1980s the Jordan River and its environs have come to be thought of as an urban oasis, offering a variety of recreational activities such as the International Peace Gardens, jogging and equestrian trails, fishing, canoeing, a water slide, a model airplane park, golf courses, and other attractions.

The Provo River is located in Utah County and Wasatch County, Utah. It rises in the Uinta Mountains at Wall Lake and flows about 71 miles (114 km) southwest to Utah Lake at the city of Provo, Utah. The two main branches of Provo River are the North Fork Provo River and the South Fork Provo River. The river is impounded by Jordanelle Reservoir at the north end of the Heber Valley. Deer Creek Dam further impounds the Provo River with Deer Creek Reservoir, built-in 1941. The two branches of Provo are split into upper, middle, and lower sections. The upper Provo originates in the high Uintas and flows into Jordanelle Reservoir. Below the dam of Jordanelle to Deer Creek Reservoir is known as the Middle Provo River. The Middle Provo is joined on the right by Snake Creek, which includes the Midway Fish Hatchery. The lower section of the Provo River flows out of Deer Creek Reservoir through Provo Canyon and into Utah Lake. Ute Indians called the river Timpanoquint, meaning "water running over rocks." Early settlers changed the name to Provo, after trapper Etienne Provost, for whom the city of Provo, Utah is also named. In addition to Provost, the Quebec-born fur trapper was known as Proveau, and Provot (and the pronunciation was "Provo"). The old name for the river was instead given to the mountain to the north, which later became known as Mount Timpanogos. In the 1930s, irrigation usage and drought had shrunk Utah Lake from 850,000 acre-feet down to 20,000, prompting a reworking of irrigation systems and the creation of the Provo River Project, later called the Provo River Water Users Association. Through the Project, river management features were added, including the Deer Creek Dam and Reservoir with a reservoir capacity of 152,864 acre-feet and Duchesne Diversion tunnel allowing water from the Duchesne River to be diverted into the Provo River at certain times. The Association today maintains and operates these control and irrigation systems and monitors water flows. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), variant names for Provo River include Tim-pan-o-gos River and Upper Provo River.

The San Juan River, named by the Spanish San Juan Bautista (Saint John the Baptist), threads its way through Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah to the border of northern Arizona. With its headwaters in the San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado from which comes ninety percent of its flow, the river still drains nearly sixteen million acres of the Four Corners region as it drops from an altitude of 14,000 feet to approximately 3,600 feet above sea level. The flow of the river today is largely controlled by the waters released from Navajo Dam in New Mexico into the San Juan. The river's Utah portion is approximately 125 miles long; it then terminates as it flows into Lake Powell. The river historically has played an important part as a continuous source of water in an arid climate. Anasazi ruins and rock-art panels dot its sandstone cliffs and floodplains. The San Juan also plays a significant role in Navajo mythology, where it is known as Old Age River, One-With-a-Long-Body, or One-With-a-Wide-Body, and is characterized variously as an old man with hair of white foam, a snake coiled at the Goosenecks, a flash of lightning, and a black club of protection. This latter theme is important to the Navajos, who, even before the river became an official reservation boundary in 1884, viewed it as a line of separation between their safe confines and the land of the Utes and white men. The first substantial Anglo settlement on the Utah portion of the San Juan occurred at Riverside (Aneth) in 1878-79 when eighteen families from Colorado established a small community more than a year before the Mormons made their trek through the Hole-in-the-Rock and settled Bluff. Through the 1880s and early 1890s, trading posts flourished as Navajos herded sheep and planted small horticultural plots while the settlers struggled to prevent destructive flooding. In addition to agriculture, the San Juan has been the focus of a variety of economic endeavors. During the 1890s and early 1900s, there were futile attempts to find gold and the beginning of an interest in oil. Oil companies in the 1920s started drilling in earnest, giving rise to a petroleum industry that is still in operation today near the river towns of Aneth, Montezuma Creek, Bluff, and Mexican Hat. By the 1940s Norman Nevills and Jack Frost dominated the river-running business and took hundreds of tourists down the San Juan. This industry continues to grow, and the Bureau of Land Management has had to restrict in an attempt to keep the river experience safe and enjoyable for all.

The Sevier River drains a 5,500-square-mile portion of the mountainous desert transition zone between the eastern border of the Great Basin and the Colorado Plateau. The Sevier flows about 240 miles north from Garfield County through desert lands before it bends west and then south to empty into the mostly dry bed of Sevier Lake in West Millard County at the end of its 325-mile length. During historic times, the Native Americans known as Paiutes and Goshutes have occupied the drainage. When the Dominguez-Escalante party came through the area in 1776, they reported the natives to be more Spanish than Indian because of their beards. The explorers' cartographer, Don Bernardo de Miera, named Sevier Lake after himself and called the river Rio Buenaventura, the "river of the good journey." The Sevier takes its name from an appellation by the Spanish trappers Moricio Arce and Lagos Garcia, who came from Taos in 1813 to trade with the Utes around Utah Lake. Escaping south after troubles with the Utes, they said they traveled to the "Rio Sebero" (also reported as Severo or Seviro--Spanish for "severe" or "violent"). Trapping was popular in the region until about 1830. The river is on the California leg of the old Spanish Trail, a trade route which joined Santa Fe to the west coast; it arched north into the Great Basin to avoid the impassable barrier of the lower Colorado River. Settlement of Utah territory by whites began in 1847 and led to colonies in the region both north and south. In 1850 Mormon settlers were sent by Brigham Young to the Sevier River Valley. Native Americans in the area felt threatened when settlement encroached, and an altercation between settlers and Indians in 1852 left four Indians dead in Salina. At the same time, coming west through Salina Canyon on a railroad route survey was a government party led by John W. Gunnison. The surveyors were caught in an early morning ambush by vengeful Indians, who killed Gunnison and six of his crew. Irrigation near the mouth of the river started with settlement in 1859 in west Millard County. Obtaining water for irrigation was the most significant challenge for settlers in the semi-arid land. Uncontrolled flooding caused downstream irrigators to abandon many dams before they were finally permanently established in 1912. After floods, upriver diversions were the next most vexing challenge. The Higgins Decree of 1900 divided the waters of the lower Sevier at Vermillion Dam and established a commission to adjudicate user rights. Other decisions followed until 1936, at which time the Cox Decree finally allotted all the water of the Sevier River. It is one of the most used rivers in the United States. Less than 1 percent, or 44,840 acre-feet, of the total precipitation is not consumed. Consumption is about 1,100,000 acre-feet annually.

The Paria River is a 95-mile long tributary of the Colorado River in southern Utah and northern Arizona. It is formed in southern Utah in southwestern Garfield County from several creeks that descend from the edge of the Paunsaugunt Plateau meeting just north of Tropic, Utah. It flows across Kane County and Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument. Along the Arizona state line it descends through the Vermilion Cliffs in the Paria Canyon and onto the Paria Plateau. It joins the Colorado from the northwest approximately 5 miles southwest of Page, Arizona and the Glen Canyon Dam. The lower 20 miles of the river are within the Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness which is administered by the Bureau of Land Management. The Paria is essentially a large creek and is not navigable. The Paria is one of the most popular destinations for canyoneering in the region. Buckskin Gulch a side canyon along the river in the narrows section is considered to be one of the longest and deepest slot canyons in the United States. The Paria is also home to several important historical, geological, and biological resources. Lee's Ferry and the adjoining settlement are located within the canyon upstream of the confluence with the Colorado River with several other abandoned settlements further north. The Paria and several nearby rivers and canyons also are the site of several well preserved specimens of Native American petroglyphs, prehistoric drawings, and symbols carved into stone. The Paria boasts a vibrant desert riparian habitat that is home to several sensitive and endangered species and is also the location of Wrather Arch the longest natural arch outside of Utah.

The Price River is a 137 mile long southeastward flowing river in Carbon, Utah and Emery counties in eastern Utah. It is a tributary to the Green River. The river's early name was the White River but it was changed in the summer of 1869 when LDS Bishop William Price explored the region and renamed it making the White River above Colton into a tributary of the Price River. The town of Price was later named after the river. The Price River watershed comprises 1,900 square miles. The Price River originates at Scofield Reservoir in the Wasatch Plateau in Carbon County in central Utah. From the reservoir the river flows briefly eastward and northeastward into Utah County where it receives the flows of the White River at Colton. Historical accounts place the origin of the Price River at the confluence of the White River and Fish Creek, such that lower Fish Creek continued from below Scofield Dam. The White River drains the Tavaputs Plateau. From Colton the Price River continues southeastward receiving Beaver Creek and then Kyune Creek. Below Kyune the river enters Price Canyon and drops back into Carbon County alongside HWY6. The canyon of the Price River is a physiographic break between the Wasatch Plateau and the Book Cliffs. Then the Price River receives Willow Creek at Castle Gate. Willow Creek is the largest tributary in the Book Cliffs area. After leaving Price Canyon at Heiner the Price River enters the city of Helper and then Price. From Price the river continues southeast along the northeastern edge of the San Rafael Swell at which point it proceeds east into canyonlands joining the Green River in Gray Canyon about 20 miles north of Green River, Utah.

The Weber River is a 125 mile long river. It begins in the northwest of the Uinta Mountains and empties into the Great Salt Lake. The Weber River was named for American fur trapper John Henry Weber. The Weber River rises in the northwest of the Uinta Mountains at the foot of peaks including Bald Mountain, Notch Mountain, Mount Marsell, and Mount Watson. It passes by Oakley, and fills the reservoir of Rockport Lake then turns north receiving the flow of major tributaries Silver Creek at Wanship and Chalk Creek at Coalville. Coalville is also at the upper end of Echo Reservoir. Below the reservoir the river passes Henefer turns more westerly and then passes Morgan where it receives East Canyon Creek. Issuing out of the mountains at Uintah at the mouth of Weber Canyon it turns north again where it is joined by the Ogden River west of Ogden. The combined stream meanders across mostly-flat land entering mud flats near where it empties into the Great Salt Lake contributing about 25 percent of the total water entering the lake.

The San Rafael River is a tributary of the Green River approximately 90 miles long in east central Utah. The river flows across a sparsely populated arid region of the Colorado Plateau and is known for the isolated scenic gorge through which it flows. The river rises in northwestern Emery County approximately 5 miles southeast of Castle Dale by the confluence of Cottonwood, Huntington and Ferron creeks which provide its headwaters in the Wasatch Plateau region. It flows east-southeast along the north side of the Coal Cliffs and the prominent anticline called the San Rafael Swell passing north of Window Butte and through two narrow slot canyons in Coconino Sandstone called the Upper and Lower Black Box. This area is known as the San Rafael Gorge sometimes called the "Little Grand Canyon" a few miles upstream where the San Rafael passes between the Wedge on the north and Sid's Mountain and No Man's Mountain on the south. After passing through the San Rafael Reef it enters the 15 mile long San Rafael Valley where it joins the Green River from the west approximately 10 miles south of the town of Green River. The San Rafael is the last major tributary of the Green River before it joins the Colorado River in Canyonlands National Park.

The oldest and most visited national park, Zion National Park is located in southwestern Utah. Zion Canyon is located on the southern part of the Markagunt Plateau. It is cut by tributaries of the Virgin River which have left eroded canyon walls and monoliths that are beautiful and overpowering. Zion Canyon presents a diverse collection of nature's wonders that include such features as the towering and magnificent 2,200-foot Great White Throne, the park's most famous landmark; the Court of the Patriarchs; the Sentinel; the Watchman; Checkerboard Mesa; Kolob Arch, at 310 feet the world's largest known natural span; and the Narrows of the Virgin River, where a person can walk upstream to places so narrow that both sides of the canyon walls can almost be touched with one's outstretched hands.

ASPEN TREES

In the Fishlake National Forest in Utah, a giant has lived quietly for thousands of years, and may be one of the oldest living things on the planet. The Trembling Giant, or Pando, is an enormous grove of quaking aspens that is a single organism. Each of the approximately 47,000 or so trees in the grove is genetically identical and all the trees share a single root system. While many trees spread through flowering, quaking aspens usually reproduce by sprouting new trees from the expansive lateral root of the parent. The individual trees aren’t individuals but stems of a massive single clone, and this clone is truly massive. Pando is a Latin word that means I spread. Spanning 107 acres and weighing 6,615 tons, Pando is thought to be the world’s largest organism and is almost certainly the most massive. Estimates of Pando's age have it as over one million years old, which would easily make it one of the world’s oldest living organisms. The quaking aspen is named for its leaves, which stir easily in even a gentle breeze and produce a fluttering sound. One of the most popular seasons to visit Pando is fall when the leaves turn bright yellow.

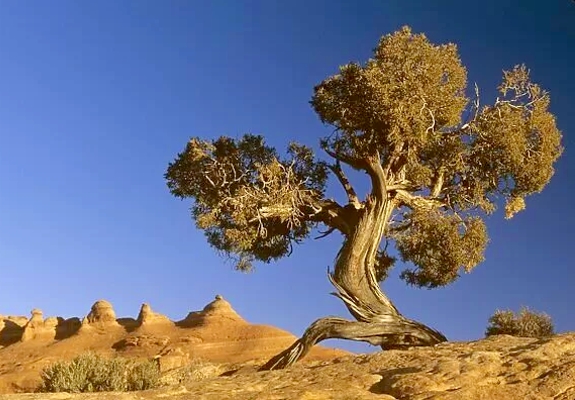

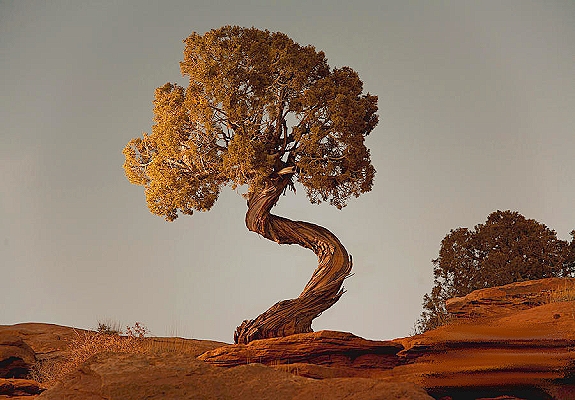

JUNIPER TREES

Among the majestic mountains, spires, canyons, buttes, and mesas of Utah can be found a truly amazing tree: Junipers grow in some of the most inhospitable landscapes imaginable, thriving in an environment of baking heat, bone-chilling cold, intense sunlight, little water and fierce winds than can kill any other tree. They stay alive because of a massive root system that often appears to grow straight out of solid rock as the roots can tunnel down 100 feet to find water. Junipers typically live up to 700 years. No two junipers ever look alike. Animals find the juniper very inviting. The berries are edible, though they are not as popular as pine nuts. However, juniper berries are a staple for jackrabbits, coyotes, and a variety of birds. This is important for the tree as well since it helps to disperse its seeds. It's wood is rot-resistant. Their oddly twisted trunks, with branches pointing in all directions, have a mystical quality. Each tree is like a work of art. It provides a wonderful contrast to the lifeless rock or cliff. Species include: Utah juniper - Rocky Mountain juniper - Chinese juniper.

JOSHUA TREES

The Joshua tree is a subgroup of flowering plants that also includes grasses and orchids. Mormon immigrants had made their way across the Colorado River, and these pioneers named the tree after the biblical figure Joshua, seeing the limbs of the tree as outstretched in supplication. Judging the age of a Joshua tree is challenging. These trees do not have growth rings like other trees. Some researchers think an average lifespan for a Joshua tree is about 150 years. The Joshua tree is also capable of sprouting from roots and its branches.

COTTONWOOD TREES

A cottonwood tree soars and spreads, growing more than 100 feet tall and almost as wide. It’s a cherished shade tree, often planted in parks. In the wild, cottonwood grows along rivers, ponds and other bodies of water. It also thrives in floodplains and dry riverbeds, where infrequent rains transform dry land into waterways. Fast growth and wonderful shade are reasons enough to cherish cottonwood, but these trees possess other qualities that make them worth planting. The leaves have flat stems, so they shimmer and rustle in the wind. The effect is eye-catching and distinctively attractive. The tree offers strong fall color, with leaves fading to glowing shades of gold. You will see Fremont and Black Cottonwood trees in Utah. Native Americans used cottonwood trees for dugout canoes and even transformed its bark into a medicinal tea. Species include: Fremont cottonwood - Narrowleaf cottonwood - Lanceleaf cottonwood - Black cottonwood - Eastern cottonwood.

OTHER TREES FOUND IN UTAH

(GINKGO) Ginkgo maidenhair (PINE) Limber pine - Southwestern white pine - Bristlecone pine - Colorado pinyon - Singleleaf pinyon - Ponderosa pine - Lodgepole pine - Austrian pine - Scotch pine (CEDAR) Atlas cedar - Northern white cedar - Western red cedar (SPRUCE) Engelmann spruce - Colorado blue spruce - Black Hills spruce - Alberta spruce - Norway spruce (FIR) Douglas fir - White fir - Alpine fir (REDWOOD) Dawn redwood (CYPRESS) Bald cypress - Italian cypress - Arizona cypress - Hinoki cypress (WILLOW) Peachleaf willow - Black willow - Crack willow - Weeping willow - Navajo willow (POPLAR) Balsam poplar - Yellow poplar White poplar - Lombardy poplar - Carolina poplar (WALNUT) Black walnut - Arizona walnut - English walnut (BIRCH) Water birch - European white birch - Paper birch (BEECH) European beech - American beech (OAK) Rocky Mountain oak - Wavvleaf oak - Bur oak - Mossycup oak - White oak - Northern red oak - English oak (ELM) American elm - English elm - Siberian elm - Chinese elm - Lacebark elm (MULBERRY) Red mulberry - White mulberry (MAGNOLIA) Saucer magnolia - Star magnolia (SYCAMORE) American sycamore (ROSE) Choke cherry - Purpleleaf plum - Myrobalan plum - European bird cherry - Sour cherry - Sweet cherry - Sargent cherry - Japanese cherry - Higan cherry - Peach - Apricot - Apple - Crabapple - Callery pear - Ussurian pear (ASH) European mountain ash - Greene mountain ash - American mountain ash - Korean mountain ash - Singleleaf ash - Modesto ash - Green ash - Blue ash - White ash (MAHOGANY) Curlleaf mountain mahogany (HAWTHORN) Douglas black hawthorn - Cockspur hawthorn - Washington hawthorn - Lavalle hawthorn - English hawthorn - Green hawthorn (LEGUME) Honey mesquite - Mimosa silk tree - Eastern redbud - California redbud (LOCUST) New Mexican locust - Black locust - Idaho flowering locust - Honey locust (MAPLE) Manitoba maple - Canyon maple - Rocky Mountain maple - Norway maple - Sugar maple - Black maple - Silver maple - Red maple - Amur maple (BUCKEYE) Horse chestnut - Red horse chestnut - Ohio buckeye - California buckeye (LINDON) American linden - European linden - Crimean linden - Silver linden (DOGWOOD) Red osier dogwood - Kousa Dogwood - Pagoda dogwood - Cornelian cherry dogwood

Explore Utah was created and is maintained by Explore Utah Online ©2020-2025 (All Rights Reserved) This website was created for the enjoyment of Utah. If you believe copyrighted work is available on this website in a way that constitutes a copyright infringement please contact me for removal. All rights to the images and other materials used belong to their respective owners. I do not claim ownership over any third-party content used. Photos on this website are used for educational purposes only and used with permission and courtesy of: Scott Taylor - Albert Wirtz - Angela Banfield - Catherine Colella - Chase Bartholomew - Danielle Yung - Elliott Hammer - Francisco Ovies - George Gibbs - Greg Kebbekus - Hilary Bralove - Jacob Moogberg - Jim Paton - Jim and Nina Pollock - John Dahlstet - Jay Luber - Jessica Holdaway - John Hammond - John Dahlstet - Logan Selinski - Logan Selinski - Michelle Leale - Mae Thamer - Mark Thompson - Mia & Steve Mestdagh - Michelle Leale - Randy Baumhover - Sven Hähle - Shawn Anthony - Thomas Eckhardt - Thomas Jundt - University Of Utah - Bureau of Land Management - Utah Education Network - Utah History Encyclopedia - Utah League of Cities and Towns - Utah Geological Survey - Ski Utah - Free To Use Photo Websites: Unsplash - Pexels - Freepik - Pixabay - iStock - ShutterStock - Burst - Flickr - PickPik - Rawpixel - HistoryPictureArchive This website contain links to third party websites. The linked sites are not under the control of this website and is not responsible for the contents of any linked website. These links are provided as a convenience only and shall not be construed as an endorsement of, sponsorship of, or affiliated with the linked website ... Send your comments or questions to webmaster@exploreutah.online